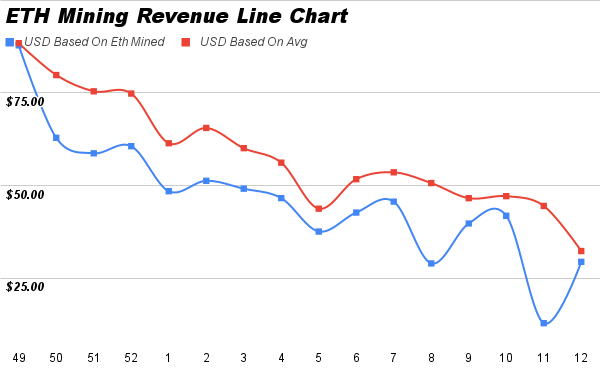

Study comparing the revenue of a personal Ethereum miner in US Dollars (USD) to the average rate of Ethereum mining revenue relative to megahash, over November 28th, 2021 to March 18, 2022. Average weekly Ethereum mining revenue rate in USD per megahash, weekly personal Ethereum revenue, and the price of 1 Ethereum was collected over 15 weeks to calculate average Ethereum mining revenue and personal mining revenue per week in USD. Results depict higher revenue in the average rate of Ethereum mining compared to the personal Ethereum miner relative to megahash.

Ethereum (ETH) mining revenue is nothing new, yet still a practice new to so many. Blockchain technology provides operability of ETH’s network and has become a passion that I participate in through ETH mining. Revenue analysis of personal mining operations in comparison to the reported network average would reveal whether my machine outperformed the network in revenue relative to megahash. This study inspects the relationship of revenue in USD between the personal ETH miner and the reported ETH mining average.

ETH is a cryptocurrency, currently operating under a Proof of Work (PoW) mechanism governed by the algorithm Ethash. PoW is a decentralized consensus protocol, in which miners: do the work- direct validation within the ETH ecosystem and provide proof of their work. ETH miners provide a “certificate of legitimacy” for transactions, balances, and market orders. The miner "independently agglomerates a set of valid transactions into a block and attempts to solve a predefined cryptographic puzzle as PoW, which involves data from the block and a specific prior block. The first miner to solve the problem broadcasts his solution to the network, and by virtue of the solution, is able to add the block to the ever-growing blockchain as a child of the prior block." (Bissias et al., 2019)

Anyone is capable of mining with a computer, internet connection, electricity, and money for graphic processing units (GPUs). Users can use this capacity for revenue to create profits through proper management of hashrate, electric rate, and power consumption.

Hashrate is primarily dependent on the hardware used. Hashrate defines the miner’s performance rate, the higher the more revenue. "Based on the number of shares a miner submits over a specific time period, the miner’s hash rate can be derived. Hash rate refers to the number of unique attempted PoW solutions generated over a period of time" (Knottenbelt et al., 2018). A specific hashrate may earn less as more miners come online, and new components outdo prior models. This change is termed an ‘increase in network difficulty’, in turn reducing mining revenue.

Electricity is a priority when computing profitability but disappears when it comes to revenue. It’s possible to earn revenue without profit, if the electric bill is larger than ETH payouts, you are paying more than you are earning. It’s important to compute electric rate and consumption when considering profit. The present study is concerned with revenue, not profitability, so electric consumption will not be considered.

Many operating systems allow ETH mining, including Windows. While other operating systems are designed specifically for Proof of Work, like Hive OS. Miners are rewarded through participation, if a new block is solved/ created, two ETH are minted to the miner. Due to intense difficulty to participate in the worldwide network as a solo miner, most miners opt towards joining a mining pool (group mining). Countless pools exist, as well as payment methods to distribute among participating miners. Before having a pool to mine with mining software is required. Various options are widespread furthering decentralization in the network including Phoenix Miner, NBMiner, and GMiner.

Revenue is acquired through block rewards and transaction fees. A block in ETH is a batch of transactions which allows for validation of dozens of transactions to be synchronized at once. Blocks contain a reference to its parent block, and all are chained together to the first genesis block. "Block time refers to the time it takes to mine a new block. In Ethereum, the average block time is between 12 to 14 seconds and is evaluated after each block." (Smith, 2022)

Understanding the relationship between personal ETH mining revenue and the reported ETH mining revenue average can help answer individual questions and concerns regarding mining's value. For example, how average revenue trends relate to personal profits relative to hashrate, discover inefficient mining practices, and develop a deeper understanding of ETH mining difficulty to profitability. To fulfill the performance of a full-time miner, one must truly become a full-time miner. Meaning not taking away mining time from the machines. As a college student extraneous variables enter the situation making providing that of a full-time miner becomes distant. I hypothesize personal ETH miner revenue will perform lower overall in comparison to reported average ETH mining revenue.

Around 170 megahash is reached by the personal ETH miner. Which consists of 4 GPU’s: 2x Nvidia GeoForce RTX 2080 8gb, and 2x Nvidia Geforce RTX 3060Ti LHR. Internet access is gained through a wired connection into a wireless router extender. The miner uses Hive OS to operationalize the machine, Nbminer as the miner, and Ethermine for the pool.

Hive OS is a computer operating system optimized for mining of cryptocurrencies. Nbminer, one of many miners, provides extra efficiency for LHR cards making it an understandable miner option. Ethermine, the mining pool within this study, offers a PPLNS payout scheme, “Pay-Per-Last-N-Shares”. When a block is found the reward of each miner is calculated based on the participation to the last number of pool shares. Ethermine provides instant payouts as soon as the threshold of 0.005 ETH is met.

BitInfoChart aggregates a historical chart of ETH’s mining profitability in USD per day for one megahash. Multiple timelines are available with daily data points from 3-months to 3-years to even all-time (7/30/15).

15 weeks of personal mining revenue was gathered from November 28th, 2021 (Week 48, 2021) to March 18, 2022 (Week 12, 2022) with a mining rig averaging 170 megahash through Ethermine. Data was grouped weekly Sunday-Saturday, with the United States Dollar (USD) price of 1 ETH listed for the corresponding week. Revenue in ETH was multiplied with the price of 1 ETH each week to create a weekly estimate of personal miner revenue in USD.

Reported average daily mining revenue collected on BitInfoChart was transformed into weekly revenue averages in USD per 1 megahash. To create an estimate of reported average mining revenue in USD relative to the hashrate output of the personal miner, weekly avg USD per 1 megahash was multiplied with 170.

A conducted on SPSS comparing personal mining revenue in USD (M= 46.51, SD= 16.81, N= 16) and reported average revenue in USD (M= 58.23, SD= 15.12, N= 16) revealed a significant difference in revenue; t(15)= 6.1, p = .001. Results fail to reject the hypothesis; Personal ETH miner revenue will perform lower overall in comparison to reported average ETH mining revenue. Proving the personal miner is under performing based on the average reported revenue.

Visual analysis depicts clear discrepancies each week in ETH mining revenue between personal and reported rates. The initial revenue found in the first week, week 49 2021, is the closest the two values are throughout the whole study, a 0.58 cent difference. The line chart displays the downward trend of ETH mining revenue over the course of the study. Based on visual analysis, revenue is lower, and drops are more significant in personal mining than in the reported average.

Findings revealed the expected hypothesis to be true, personal ETH miner revenue will be lower overall in comparison to the reported average ETH mining revenue. Revenue from mining is multifactorial, hardware could crash, electricity could be cut off, or internet connection could be lost.

Lower revenue in personal mining can be linked to an unstable mining operation. Hive OS, the operating system used for my miner is known to randomly crash forcing a mandatory physical reset. Which could leave the miner not working for hours, increasing down-time rather than ETH. Additional crashes occur when rebooting the wifi router to clear cache and speed connection. This happens often and randomly, forfeiting away a lot of potential participation. Since the personal miner is also a workstation it’s necessary to turn off the miner when there’s tasks to complete. Graphic designing, video editing, report writing, and researching take precedence over mining ETH. Additionally, playing video games for a couple hours a week takes away from operational mining time. Low overclock settings may have influenced the decrease in revenue as well. These settings are set low for hardware safety and longevity, which may negatively affect returns. Crypto’s volatility could have played a big role, if the personal miner amassed a large amount of down time while the market was booming, a lot of potential revenue could have been lost.

Results imply personal operations could be more efficient in terms of ETH mining in various measures. Whether it be up-time or hashrate, it is clear that there is still room to grow. This has shown how much potential revenue I have missed out on due to not maintaining a stable participation rate throughout the study.

Cryptocurrency mining revenue is hot in the media and in the rooms they operate. Many will go to the greatest extent to receive maximum revenue. In the comparison of personal miner revenue and the reported ETH revenue rate, a distinction is made clear of those who maximize their ability to reap revenue mining ETH and those who don’t.

Bissias, G., Levine, B. N., Ozisik, A. P. (2019). Estimation of Miner Hash Rates and Consensus on Blockchains. Cornell University, Computer Science. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1707.00082

Knottenbelt, W. J., Pritz, P. J., Werner, S. M., Zamyatin, A. (2019). Uncle Traps: Harvesting Rewards in a Queue-based Ethereum Mining Pool. VALUETOOLS 2019: 12th EAI International Conference on Performance Evaluation Methodologies and Tools, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306309.3306328

Smith, C., (2022, January 3) BLOCKS. Ethereum. https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/blocks/