I am using the following development stack at the moment of writing this article.

Hex: 0.18.1

Elixir: 1.7.3

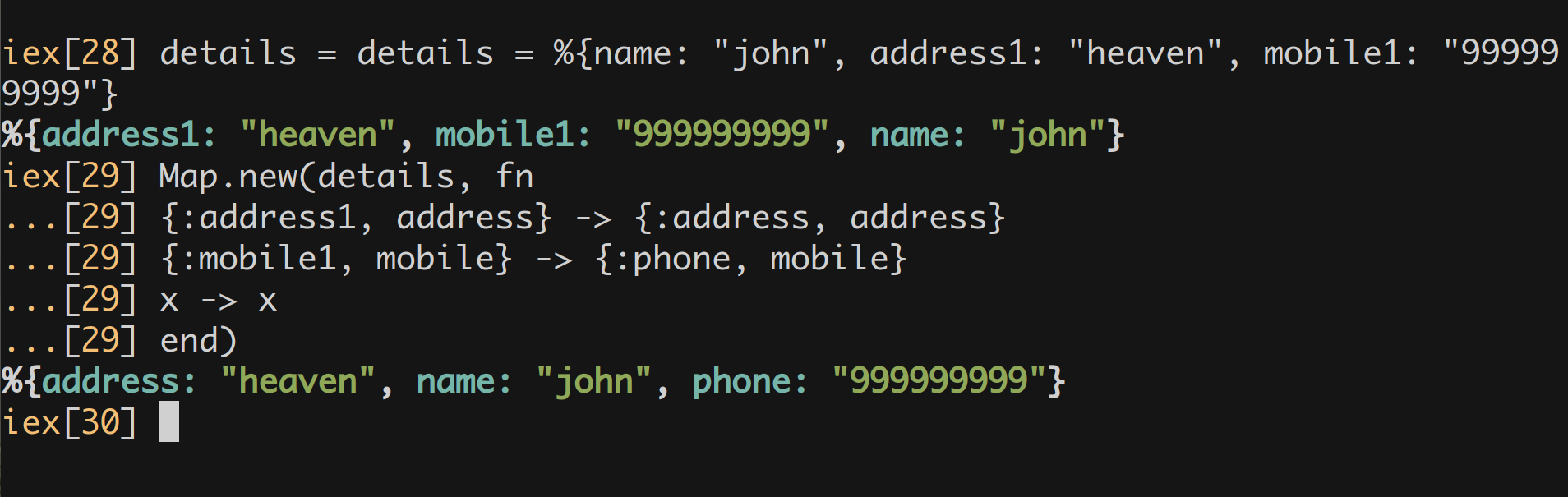

OTP: 21.1.1I know, you might be thinking why some one would do that. I too had the same feeling until I met with a requirement in one of my previous projects where I was asked to replace address1 with address and some other keys as well. It is a huge one. I have to do change many keys as well.

I’m here with a simple map to keep it understandable. But, the technique is same.

The thing to remember is; be smart and stay long;

details = %{name: "john", address1: "heaven", mobile1: "999999999"}The above map comprises of two weird keys address1 and mobile1 where we do workout on to take over them.

iex> details = %{name: "john", address1: "heaven", mobile1: "999999999"}

%{address1: "heaven", mobile1: "999999999", name: "john"}

iex> Map.new(details, fn

{:address1, address} -> {:address, address}

{:mobile1, mobile} -> {:phone, mobile}

x -> x

end)

%{address: "heaven", name: "john", phone: "999999999"} #outputNothing , just pattern_matching , the boon for functional programmers. The magic lies inside Map.new and the anonymous function where we used our magic band to see the actual logic.

This is just to know things can be done in elixir for beginners.

iex> x=5

5

iex> y=7

7

iex> {x,y}={y,x}

{7,5}

iex>x

7

iex>y

5As we know, Enum.filter will do the job based on the evaluation of a condition. But still, we can use the pattern to filter things.

Let me make you clear with the following example.

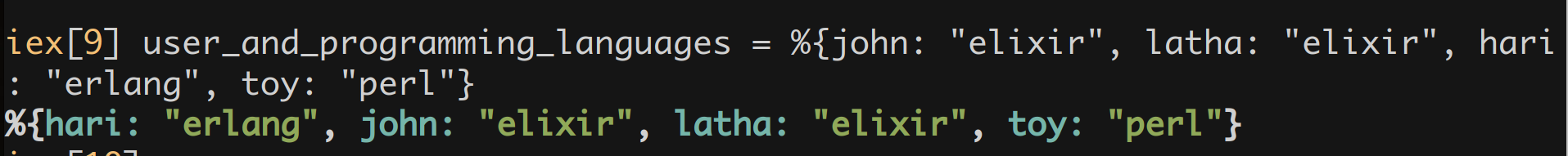

I have a list of users where their names are mapped to their preferred programming language.

iex> user_and_programming_languages =

%{john: "elixir", latha: "elixir", hari: "erlang", toy: "perl"}

%{hari: "erlang", john: "elixir", latha: "elixir", toy: "perl"}Like above, the user_names are mapped with their languages. Now, our job is to filter the users of elixir language.

Just let me know which one you do prefer after checking out the following…

iex> user_and_programming_languages |>

Enum.filter(fn {_, lang} -> lang=="elixir" end )

[john: "elixir", latha: "elixir"]

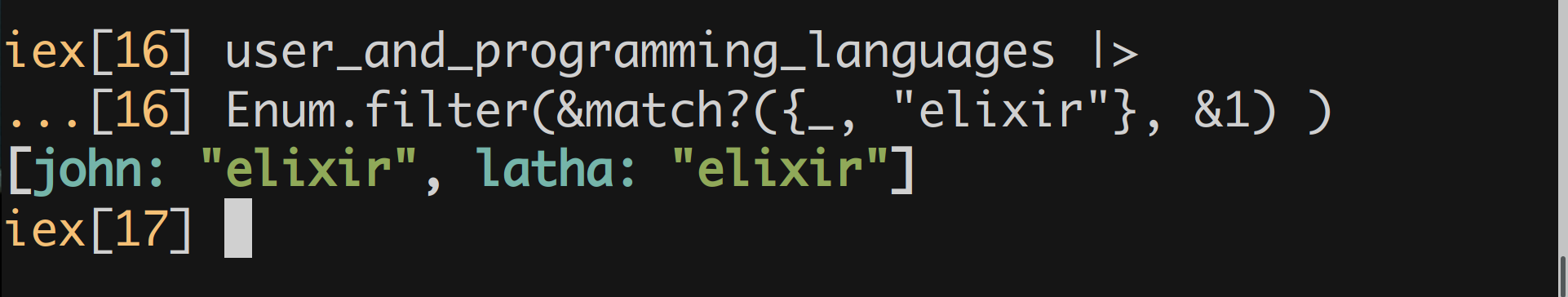

#outputOR, using match? for pattern based

user_and_programming_languages =

%{john: "elixir", latha: "elixir", hari: "erlang", toy: "perl"}

user_and_programming_languages |>

Enum.filter(&match?({_, "elixir"}, &1) )

[john: "elixir", latha: "elixir"]

#outputCheckout the screenshots of evaluation

I took the simpler lines of code to give a demo of using match? but, it’s usages are limit less. Just think about the pattern and match over it. Think out of the box guys. But don’t blow up your mind and don’t blame me for that.

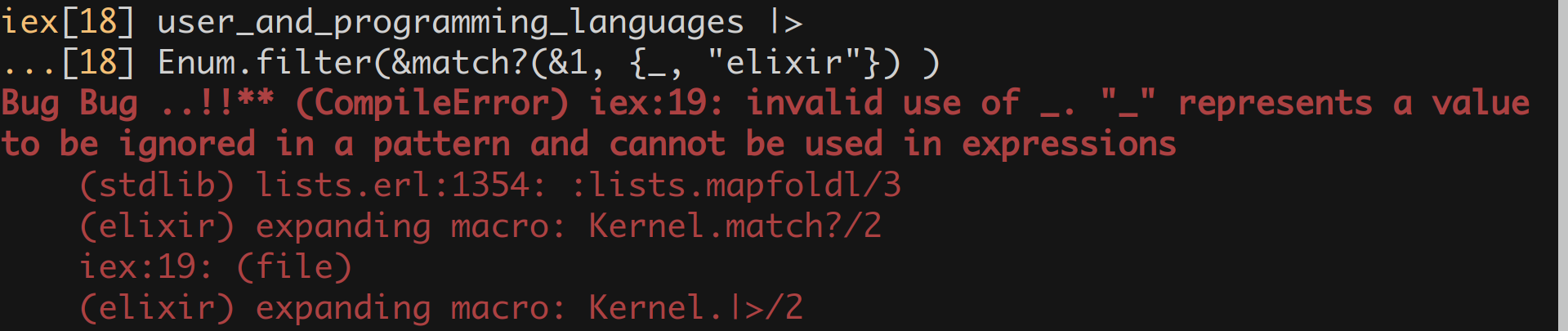

Warning:

Make sure of your pattern as the first parameter to the match? otherwise, you have to pay for the compiler. Just kidding 😃

iex> user_and_programming_languages |>

Enum.filter(&match?(&1, {_, "elixir"},) )Let’s bump for more.

As we know elixir is free language, where you can build anything you need. But, be careful It is just to show you something is achievable.

It is a LEFT and RIGHT Pipe

We usually end up with some sort of results in the format {:ok, result} . This can be found anywhere in your project sooner or later.

If you pipe it to the function obviously you will end up with an unknown expectation. I am talking about run-time errors. Our |> is not smart enough to check it for whether is a direct result or {:ok, result} .

Let’s build it for the GOD sake but not for your client.

iex> defmodule Bangpipe do

defmacro left <|> right do

quote do

unquote(left)

|> case do

{:ok, val} -> val

val -> val

end

|> unquote(right)

end

end

endThis Bangpipe I mean <|> is defined to do the task. Before sending the result to the function in right, it is performing the pattern matching over the result to identify what kinda result it is. I hope you understood what actually the result I am talking about. The Secret behind Elixir Operator Re-Definitions : + to - *Just for Fun*

We can also do re definitions on elixir operators. Check above URL.

How to use ❓

Just import Bangpipe the left-right pipe will be loaded. Copy and paste to experience it in live and fast into iex

iex[6] import Bangpipe

Bangpipe

iex[7] data = {:ok, [1,2,3,4,5]}

{:ok, [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]}

iex[8] data <|> length

5“Good programmers write the code & great programmers steal the code” This tip is copied from the Elixir Lightening Talk

This is highly recommended command to check out what hex version is installed and how it is build with.

I have had experienced a bug in the project in my machine but not from my co-programmer though we work on the same project. The actual problem is we are using different hex versions. I come to know this by running mix hex.info in both systems. That saved a lot of time.

mix hex.infoThat gives the information about the hex and how it is built with.

Similarly, we can find the information of any package like mix hex.info package_name

mix hex.info typexYou can be more specific too by mentioning the version of the package.

mix hex.info <<package_name>> <<version>>Replace <> and <> as you required.

Let’s create a brief story here.

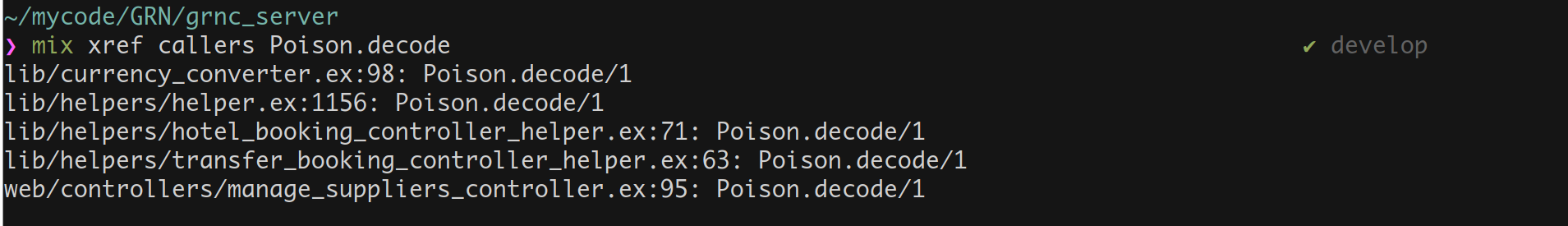

The moment when GOD’S are against you, your manager will come and give you a vast legacy project code and asked you to find out all the places where a particular function is called. In a sentence, the callers of a particular function.

What will you do? I don’t think it is a smart way of surfing in each and every file. I don’t. So, you don’t.

mix xref callers Module.function

example

mix xref callers Poison.decodePrints all callers of the given CALLEE, which can be one of: Module, Module.function, or Module.function/arity.

mix xref callers ***Module***

mix xref callers ***Module.fun***

mix xref callers ***Module.fun/3***

You can add function arity to be more specific, in this case mix xref callers Poison.decode/1 .

BOOM ! Now, you can surprise the manager with results before he reaches his cabin. Be fast and smart.

I solely experienced this when my co-worker I better say co-programmer asked for help regarding the situation but no manager in my case.

Explore more about xref

mix help **xref**You need this in rare cases to meet the type specifications while evaluating some kinda conditional code logic which results to a Boolean value.

iex[12] 5.0==5 # types are not considered here

true

iex[13] 5.0===5 # types are strict considered here

falseTo convert integer to float I just divide the value by 1 using Kernel./ .

iex[2] val = 5

5

iex[3] is_integer val

true

iex[4] val = val/1

5.0

iex[5] is_integer val

false

iex[6] is_float val

true

As you already know sigils will help us in less typing for creative stuff. Consider the following example of defining a list of strings.

sentence = ["I", "Love", "coding", "in", "elixir"]That is a lot of typing here. We can improve this without typing any " marks with the help of ~w sigil.

It returns a list of “words” split by whitespace. Character unescaping and interpolation happens for each word.

sentence = ~w(I Love coding in elixir)We can still use the interpolation as well. Suppose, I would like to make the language dynamic in the above sentence, I mean one loves elixir and other loves some other languages . So, let’s put the language in a variable lang and interpolate it over.

iex[6] lang = "haskel"

"haskel"

iex[7] sentence = **~w(I Love #{lang})**

["I", "Love", "haskel"]

iex[8] lang = "Rust"

"Rust"

iex[9] sentence = ~w(I Love #{lang})

["I", "Love", "Rust"]What if you don’t want the interpolation? just use ~W a capital form.

iex[10] sentence = ~W(I Love #{lang})

["I", "Love", "\#{lang}"]I have a collection of hotel_bookings and I need to group them based on their booking status.

To keep this simple, I am just using some false random collection.

iex> hotel_bookings = [

%{name: "John", country: "usa", booking_status: :success},

%{name: "Hari", country: "india", booking_status: :fail},

%{name: "Mahesh", country: "austria", booking_status: :pending},

%{name: "Ruchi", country: "paris", booking_status: :success},

%{name: "Nitesh", country: "malasia", booking_status: :success},

%{name: "Manoj", country: "japan", booking_status: :fail},

%{name: "Akhilesh", country: "china", booking_status: :pending},

%{name: "Rajesh", country: "india", booking_status: :fail},

%{name: "Payal", country: "london", booking_status: :success},

%{name: "Kumar", country: "france", booking_status: :fail}

]Let’s group the things.

iex> Enum.group_by(hotel_bookings, &Map.get(&1, :booking_status))

%{

fail: [

%{booking_status: :fail, country: "india", name: "Hari"},

%{booking_status: :fail, country: "japan", name: "Manoj"},

%{booking_status: :fail, country: "india", name: "Rajesh"},

%{booking_status: :fail, country: "france", name: "Kumar"}

],

pending: [

%{booking_status: :pending, country: "austria", name: "Mahesh"},

%{booking_status: :pending, country: "china", name: "Akhilesh"}

],

success: [

%{booking_status: :success, country: "usa", name: "John"},

%{booking_status: :success, country: "paris", name: "Ruchi"},

%{booking_status: :success, country: "malasia", name: "Nitesh"},

%{booking_status: :success, country: "london", name: "Payal"}

]

}This is well and good but I need only name in the list instead of map. I mean some thing like %{fail: ["Hari", "Manoj"], ...}

We just need to tell the group_by what to return in return of grouping

iex> Enum.group_by(hotel_bookings, &Map.get(&1, :booking_status), &Map.get(&1, :name))

%{

fail: ["Hari", "Manoj", "Rajesh", "Kumar"],

pending: ["Mahesh", "Akhilesh"],

success: ["John", "Ruchi", "Nitesh", "Payal"]

}mix test --failedIn a project, there will be many programmers who write different modules. It will hard to find who has written what.

To keep the track of such things, we can add metadata to the @moduledoc . So, we come to know the developer whom we can blame to queries that hit to your mind and kept eating it while using the module.

@moduledoc "Wrong code leads you to the right bug "

@moduledoc authors: ["blackode", "doe"], since: "1.1.2"