Solves arbitrary KenKen puzzles, by representing the game as a Constraint Satisfaction Problem (CSP).

Most Constraining Variable (MCV) and Least Constraining Value (LCV) heuristics are used to backtrack from a solution and return all other possible solutions for a given puzzle.

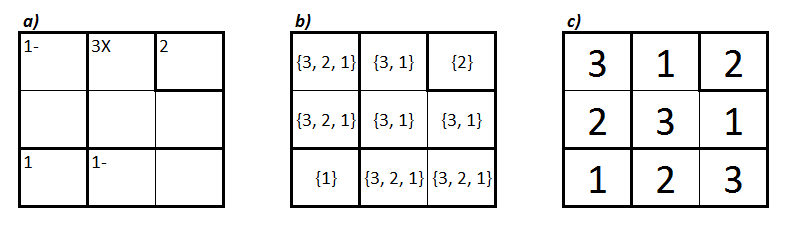

The KenKen board is represented by a square n-by-n grid of cells. The grid may contain between 1 and n boxes (cages) represented by a heavily outlined perimeter. Each cage will contain in superscript: the target digit value for the cage followed by a mathematical operator. Each cell may contain any one of the digits: 1through n inclusive. Please refer to Figure 1a for an example KenKen board representation.

Figure 1: Sample KenKen puzzle board of size 3-by-3.

The input format used to textually describe a puzzle is:

Cage_target_1 Cage_operator_1 square_index_1 square_index_2 ... square_index_n

Cage_target_2 Cage_operator_2 square_index_1 square_index_2 ... square_index_n

Cage_target_3 Cage_operator_3 square_index_1 square_index_2 ... square_index_n

...

Cage_result_M Cage_operator_M square_index_1 square_index_2 ... square_index_n

For example, the text representing the Figure 1a puzzle is:

2.0

2-14

6*25

3/36

2/78

N := n2 “number of cells in grid”

X := [0, ... , N-1]

D := [1, ... , n]

C = [

[for Row r in AllRows AllDiff(AllCellsInRow(r))],

[for Column c in AllColumns {AllDiff(AllCellsInColumn(c))}]

[for Cage a in AllCages (

TargetNumberForCage(a) == ApplyCageCageOperator(OperatorForCage(a), AllCellsInCage(a))

)]

]It is implied that the ApplyCageCageOperator function from above takes into account the non-commutative properties of subtraction and division: subtraction and division operations are performed on only cages of size 2 and only in the order that results in a positive whole number. Additionally, cages of size 1 and containing no explicit operator are meant to contain only the target value. Please refer to Figure 1c for a constraint satisfied solution to Figure 1a.

Naïve search approaches ignore the commutativity property of this CSP (and all others CSPs): the order of applying values to each cell does not matter. Additionally, pieces of the KenKen puzzle can be quickly solved by inference; by performing a slow brute-force naïve search approach, we would be ignoring following properties of this type of CSP:

- Node consistencies of cells given their cage’s target value and operator.

- Arc consistencies between cells of known value and their other corresponding row and column cells.

- Path consistencies of cells outside of a cage but in the same row or column of 2 or more cage cells containing a more constrained domain than the exterior cell.

- For example: Cell (1,0) in Figure 1b is constrained to 2 only because the two cells (1,1) and (1,2) can only each contain either 3 or 1, removing the possibility of a 3 or a 1 anywhere else in row 1.

Backtracking is able to find the solution more efficiently by cutting off potentially deep branches that will ultimately lead to failure by checking value assignments with domain consistencies (at the very least). Backtracking can be made even more efficient by incorporating inference checks and informed variable and value ordering techniques such as the Most Constraining Value (MCV) heuristic.

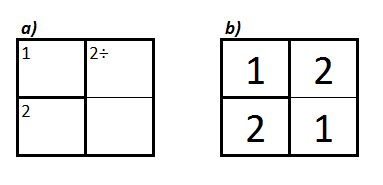

Given Figure 2a as input, there is only a single solution, as shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 2. Sample KenKen puzzle and solution.

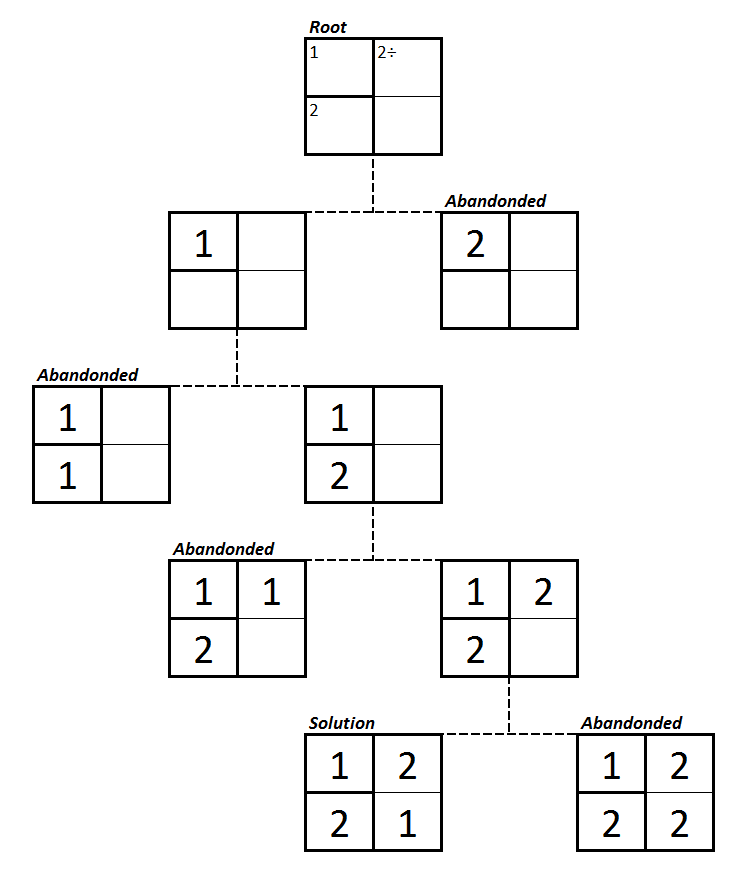

The complete solution trace of all intermediary puzzle boards that were considered during a backtracking procedure, beginning a the root node is shown below in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Backtracking procedure KenKen puzzle board trace

The MCV heuristic is crucial to an effective backtracking solution to the KenKen CSP as it provides for the mechanism to assign simple very constrained cells (Ex: single-cell-cages) first so as to create more row and column constraints when assigning the less constrained cells. For example, in Figure 1b, assigning the highly constrained cells (0,2) and (2,0) with 2 and 1 respectively cuts the domain for cell (0,0) down from {3,2,1} to {3}, which results in a similarly highly constrained cell which imposes even more constrain other neighboring cells.

If the MCV approach leaves remaining variable assignments the LCV approach can be used to efficiently search for a correct assignment by exploring values from least used in neighboring cells to most. For example, if we wanted to start the assignment process of Figure 1b beginning at cell (2,1), it makes sense to start out with 2 because choosing either 3 or 1 would limit our future assignment options for 3 other cells as opposed to just one for the 2 assignment.

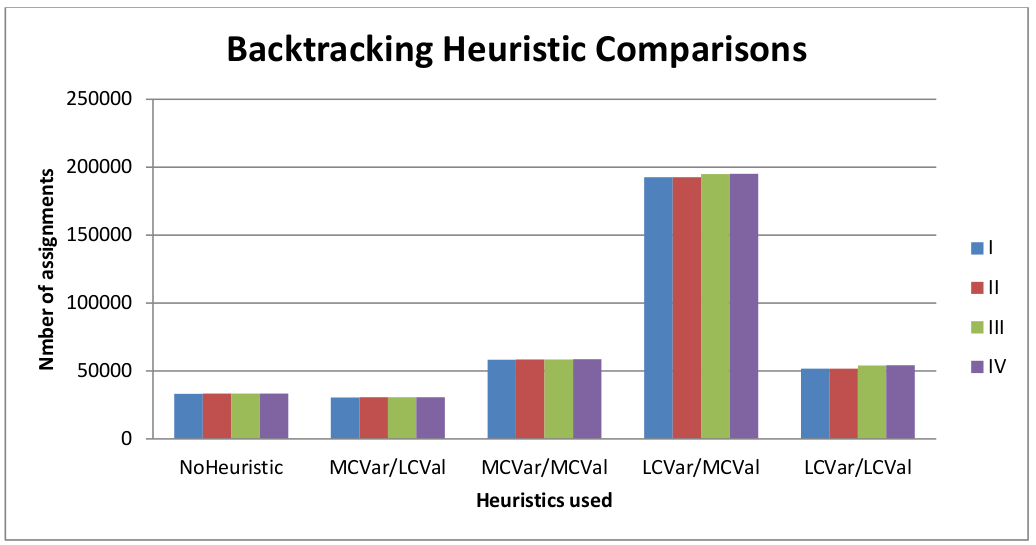

For input_example3.txt, use of the MCV and LCV heuristics results in a decrease of about 50 variable assignments with respect to the non-heuristic case, before the 1st solution (I) was found (see Figure 4). However, the reciprocal of both heuristics resulted in a significant increase in variable assignments before the first solution was found (See LCVar/MCVal in Figure 4).

Figure 4. Number of variable assignments before each solution (I, II, III, IV) was found given each heuristic combination.

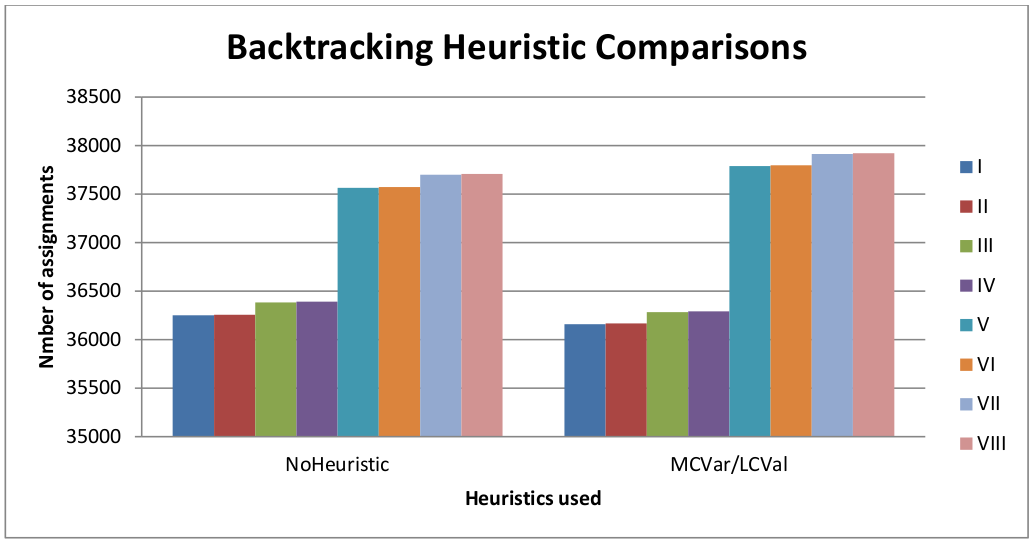

The same experiment was performed on input file: input_q3.txt as shown in Figure 5. The MCVar/LCVal heuristic combination resulted in fewer assignments required to find the first 4 solutions than the non-heuristic case. However, the MCVar/LCVal heuristic combination performed worse than the no-heuristic when finding the last 4 solutions.

Figure 5. Number of variable assignments before each solution for input_q3.txt was found, given each heuristic combination.

Compile and run KenKenPuzzleSolver [INPUT_FILE] [OUTPUT_FILE]